Earlier this year, researchers at eMarketer announced that global spend on mobile advertising is on pace to reach $31.45 billion in 2014 – an incredible 75% increase from last year. Other experts estimate that global mobile advertising spend will reach a staggering $41.9 billion by 2017.

If reality maps anywhere close to these growth projections, one thing is certain: you can expect to see a number of new faces in mobile advertising in the coming years.

If you’re new to mobile advertising, you’ve probably encountered a number of unfamiliar acronyms and an exhausting list of industry-specific terms. This vernacular phenomenon is certainly not unique to mobile advertising, as most specialized industries seem to have a language all their own.

As a new member of a rapidly-evolving, tech-savvy profession, mastering the basic concepts and breaking down important acronyms will help level off the learning curve and give you confidence to experiment with multiple mobile advertising strategies.

Wrapping your head around these ideas may feel a bit overwhelming at first, but with a little deliberate effort you’ll quickly be on track to mobile advertising guru status.

Advertiser vs. Publisher

Before getting into the acronyms and more complex industry terminology, it’s important to understand the basic relationship between two important players in the ad space: the advertiser and the publisher.

Simply put, the advertiser is the person that pays money to have advertisements shown, while the publisher is the one who gets money for showing the ads. For example, if you are promoting a product and have a banner ad you want displayed in a mobile app or on a website, you are an advertiser. On the other hand, if you have an app, blog, or website and are interested in displaying ads on your digital property, you are a publisher.

Determining whether you are an advertiser or a publisher can initially be confusing. Some of this confusion may be due to the fact that you can actually be both. For example, if you create a mobile app and pay a website to run a banner ad promoting your app, you are an advertiser (the website is the publisher). If you decide you want to allow a third-party company to pay you to display an ad in your app, you are the publisher (the third-party company is the advertiser).

It’s important to understand the relationship between the advertiser and publisher, as it plays a role in many basic industry terms.

Common Mobile Advertising Acronyms and Industry Terms

PPC: Pay per click

Pay per click (PPC) is a type of advertising campaign that is extremely common in both the online and mobile advertising space. In a PPC campaign, advertisers pay the publisher a commission each time a user clicks on the advertiser’s ad. PPC campaigns are one of the quickest ways to draw potential customers to your product or service, but it can take some time to master them. Here’s a good article for new advertisers from Entrepreneur.com, that can help you avoid common beginner mistakes and get the most out of your PPC campaigns.

CPC: Cost per click

Cost per click (CPC) is the actual amount that the advertiser pays the publisher each time a user clicks an ad in a PPC campaign. The CPC an advertiser pays is often determined through a bidding process or by a formula defined by the publisher. The formula may include factors like the value of the product being promoted, the level of keyword competition, the bidding strategy being implemented, and other related elements.

CPI: Cost per impression

The cost per impression (CPI) is the cost the advertiser pays the publisher each time an ad is displayed. Similar to CPC, the actual cost associated with each impression can vary substantially and is heavily influenced by the popularity of the app or website where the ad is displayed.

CPI: Cost per install

Cost per install (CPI) describes the amount an advertiser pays when a user installs an app. A closely related term (and used interchangeably by some advertisers), is cost per download (CPD). The key differentiator between CPI and CPD is of course the actual step of installation, as it is possible (and fairly common) for users to download an app, but never get around to installing it. As a side note, being able to determine which source is driving installs is a critical part of measuring a successful mobile advertising campaign.

CPA: Cost per action

As indicated by the name, the cost per action (CPA) is the price the advertiser pays for each occurrence of a specific action. Examples of user actions that might be measured in a CPA campaign include things like clicks, user registrations, sales, or other similar behaviors. CPA may also be used to reference cost per acquisition, though these campaigns are typically geared more towards acquiring a new user or converting a sale (as opposed to just an impression or click).

CPV: Cost per view

Cost per view (CPV) is the amount an advertiser pays each time a video is viewed by a user. Similarly, with a cost per completed view (CPCV) campaign, advertisers only pay when a user watches the entire video ad without getting impatient and skipping it.

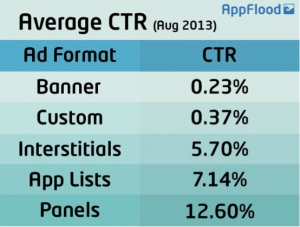

CTR: Click-through rate

The click-through rate (CTR) is a figure used to measure the effectiveness of PPC campaigns. The CTR is calculated by taking the number of ad clicks, and dividing it by the number of impressions (the number of times an ad is displayed). For example, if a campaign received 50 clicks for 20,000 impressions, the CTR would be 50/20,000 = 0.0025 or 0.25%. Advertisers spend a lot of time refining campaigns to achieve the highest CTR possible. The following chart from AppFlood, gives you a better idea of the click-through rate for different types of mobile advertising.

CPM: Cost per mille

Cost per mille (CPM) is a reference to impressions. In Latin, ‘mille’ means 1,000, so cost per mille is the cost per 1,000 impressions. Unlike PPC or CPI, which require a certain action to take place (i.e. click, app install, etc.), CPM deals exclusively with the number of times an ad is displayed, regardless of whether a click or other behavior takes place.

CR: Conversion Rate

The conversion rate (CR) is the percentage of users who completed a desired action after clicking on an ad. The desired action may be a sale or an app download. For example, if an advertiser ran an ad campaign designed to encourage users to install a mobile app, a user clicking on the ad and installing the app would be considered a successful conversion.

To calculate the CR, you take the number of conversions and divide it by the number of visitors. For example, if a campaign generated 200 installs from 7,000 visitors, the conversion rate would be 200/7,000 = .028 or 2.8%.

Maintaining a high CR can be challenging. This aggregated list of conversion case studies highlights a variety of optimization techniques advertisers use to fine-tune ads until a successful iteration is discovered.

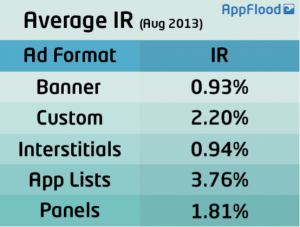

IR: Install Rate

The install rate is used to measure how many users actually download and install an app after clicking on an ad. It’s calculated by dividing the number of installs by the number of clicks an ad received. For example, if an ad received 10,000 clicks and generated 200 installs, the IR would be 200/10,000 = 0.02 or 2%. The AppFlood chart below gives you an idea of the average IR for different mobile ad formats.

ARPU: Average revenue per user

The average revenue per user is a calculation that allows advertisers to stay apprised of per-user revenue. The ARPU is calculated by taking the total revenue and dividing it by the number of users in a given timeframe.

For example, if an advertiser has an app that generated $100,000 per month from 50,000 users, the ARPU would be $100,000/50,000 = 2 or $2.00. To illustrate how the ARUP can provide insight over time, imagine a scenario where an advertiser acquires 20,000 new customers month over month.

Month 1

Total Revenue: $100,000

Number of Users: 50,000

ARPU: $2.00

Month 2

Total Revenue: $110,000

Number of Users: 70,000 (50,000 from Month 1 + 20,000 new users)

ARPU: $1.57

As you can see, the ARPU dropped from $2.00 to $1.57 ($0.43) from Month 1 to Month 2. In this example, even though the total revenue increased by $10,000, the ARPU decreased, indicating that the company is not monetizing users as effectively as they were previously.

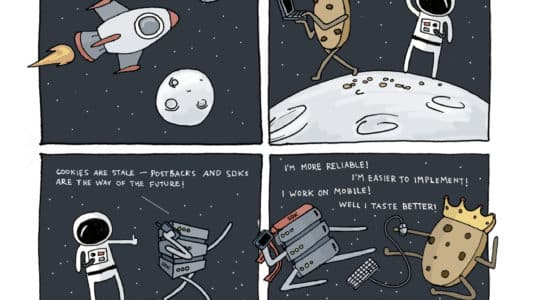

SDK: Software Development Kit

A software development kit is a programming package that enables programmers to develop applications for a particular platform. SDKs often include sample code, support documentation, library files, debugging tools, one or more APIs (more on these below), and other useful resources essential for mobile advertising.

One non-technical way to think about SDKs (borrowed from Pointroll), is to compare them to a language. For example, the English language is made up of letters, words, grammar, punctuation, and other rules. If you took that set of rules and bundled them together, that would be your “English” SDK. With this new English SDK you can now communicate various ideas and make something new. To bring it back to the technical realm, the iPhone SDK is what enables third-party programmers to create apps that run directly on the iPhone.

SDKs are typically provided for free, as companies encourage developers to create applications for their platform. For example, MobileAppTracking offers a native SDK for Android, iOS, JavaScript, and Windows Phone, enabling programmers to integrate MobileAppTracking functionality into their mobile applications on each of these platforms.

API: Application Programming Interface

An application programming interface (API) consists of programming instructions (commands, routines, functions, protocols, etc.) that specify how software components should interact with each other. APIs are all about communication, literally acting as the interface between different programs and facilitating the interaction.

For example, Google Maps is a strong example of a commonly used API. Using the programming instructions provided by the API, third-party developers are able to integrate Google Maps into their own apps. And as you can see by these examples, once Google Maps has been integrated, it can be utilized in a variety of unique ways for mobile advertising campaigns.

UDID: Unique Device Identifier

A unique device ID (UDID) is a distinctive 40 character alphanumeric string that maps to an individual iPhone, iPad, or iPod touch. To put it a little bit differently, the UDID is essentially the social security number of your iOS device. Apple uses the UDID for several purposes, including connecting a device to a user’s Apple ID.

As you might imagine, access to UDIDs can be a very useful resource to mobile advertisers. In recent years, UDIDs have been part of privacy discussions as third-party applications were able to collect UDIDs and connect them to a user’s name and other personal information. However, as of May 1, 2013, Apple no longer accepts iOS apps that collect UDIDs. Although Android does not generate a specific UDID, the platform still provides multiple options for locating a unique ID traceable to a specific device.

IDFA: IdentifierForAdvertisers

Shortly after Apple phased out UDID use, they released the identifierForAdvertisers (IDFA or IFA). The IDFA is a random serial number temporarily assigned to an iOS device that allows mobile advertisers to see what a user is viewing and serve a targeted ad. However, unlike using the UDID to gain insight into user behavior, IDFA tracking is anonymous and doesn’t show any personally identifying information to the advertiser. Using IDFA is Apple’s preferred mobile ad tracking option.

Supply- and Demand-Side Platforms

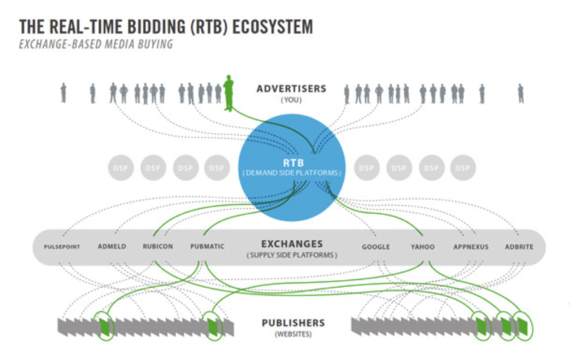

In the mobile advertising space, breaking down the supply and demand relationship can initially be a little tricky. Supply generally refers to the publisher’s inventory (the space on their website or mobile app where an ad can be displayed), the demand for the inventory is met by the advertisers. A supply-side platform (SSP) is a system designed to help publishers manage and sell their ad inventory, while a demand-side platform (DSP) is a system that enables advertisers to buy ad impressions from a large range of publisher sites.

A publisher typically uses a SSP to make their ad impressions available to an ad exchange (basically, a digital marketplace). The DSP analyzes the impressions and automatically determines which impressions are most appropriate for the advertiser (based on information known about the user). In many cases, the price of each impression is determined by a process known as real-time bidding.

Real-time bidding (RTB) is essentially an automated, instantaneous auction where advertisers bid for publisher impressions. As an ad impression loads into a user’s browser, information about the user is passed to an ad exchange. The advertisers can place a bid for the impression if the user profile matches a desired criteria. The ad from the highest bidding advertiser is then displayed on the website. Incredibly, this entire transaction occurs in the time it takes to load a webpage.

It may take some time for the relationship between publishers, SSP, ad exchanges, RTB, DSP, and advertisers to totally sink in, but the image below may help visualize how it’s all connected:

Fingerprint Matching

Fingerprint matching is a method of tracking that attempts to match conversions to ads without the use of unique identifiers. After a mobile ad is clicked, data points like country code, device brand, device model, device carrier, IP address, language, and other similar features are gathered and used to create a device profile. This profile is the device fingerprint.

Advertisers are able to look at the device fingerprint from a conversion and compare it to the device fingerprints associated with an individual ad. When a fingerprint match is found, the advertiser is able to discern which ad and which publisher are responsible for the conversion (a process known as attribution). During the fingerprint matching process, no unique identifiers are collected (a characteristic appreciated by those sensitive to privacy).

However, on the flip side, because no unique IDs are taken, fingerprinting relies on statistical estimations and has a small margin of error. MobileAppTracking documentation provides great insight into all the main mobile advertising attribution methodologies, including device fingerprinting.

Invoke URLs

An Invoke URL is a special type of URL that enables a mobile user to bypass unnecessary landing pages and instead be directed to a targeted page inside a mobile app (a concept known as deep linking).

In the past, advertisers would run mobile advertising campaigns with a standard destination URL that directed all users to the mobile website of the advertised product or an app marketplace to download the app. However, to the portion of users that already had the corresponding app installed on their device, being directed to these unnecessary pages created a less-than-ideal user experience and decreased the probability of conversion.

Invoke URLs are smart and know how to optimize the experience of each individual user. For example, if a user clicks an Invoke URL and already has the corresponding mobile app installed, they will be deep linked to a designated page inside the app. However, if a different user clicks the same link and does not have the mobile app installed, they will be directed to download the app before being forwarded to the deep linked screen inside the mobile app.

By utilizing deep linking technology, advertisers are able to create a far superior user experience, boost engagement, and increase retention.

Mobile Advertising For the Future

This list of terms is by no means comprehensive, but hopefully it provides a little insight into some of the acronyms and terminology new mobile advertisers might encounter.

For all those mobile advertising experts out there, are there any terms or concepts that were difficult for you to understand at the beginning of your career? Would you modify any of the definitions above?

Share your wisdom in the comments below.

Author

Becky is the Senior Content Marketing Manager at TUNE. Before TUNE, she handled content strategy and marketing communications at several tech startups in the Bay Area. Becky received her bachelor's degree in English from Wake Forest University. After a decade in San Francisco and Seattle, she has returned home to Charleston, SC, where you can find her strolling through Hampton Park with her pup and enjoying the simple things between adventures with friends and family.

Hi! Thanks for sharing! I will add one more advice! If you want to capitalize on the mobile experience, it is better to use one of the mobile affiliate networks that will provide you with all necessary tools and tracking instruments to help you successgfuly promote apps. Moreover, you should adjust your site or landing pages to make them mobile friendly. Take a look at site Sora.com, there are you will find a lot of interesting information about affiliate marketing.

Good post! We will be linking to this particularly great post on our site. Keep up the great writing