“The world is changed. I feel it in the water. I feel it in the earth. I smell it in the air,” elven queen Galadriel whispered in the opening of the first Lord of the Rings movie.

Change is also in the mobile industry. Mobile marketing is changing in the developed world, and it’s changing in the developing world.

And you can “feel” it in the numbers. Especially if you’re an enterprise, or a major brand.

Global mobile device usage is going to reach 5.5 billion people by 2020, according to recent Forrester Research numbers. That’s significant change — a couple billion new people — but it’s not the change I’m talking about.

Changing growth and changing models

The first key change is that the developed world is now in replacement mode, while part of the developing world is still in fast growth mode. To add to the complexity, the second key change is we see three separate models of mobile maturity surfacing throughout the globe.

The first key change is that the developed world is now in replacement mode, while part of the developing world is still in fast growth mode. To add to the complexity, the second key change is we see three separate models of mobile maturity surfacing throughout the globe.

While those models that different economies are taking to achieve mobile maturity are very different, the end results will have many similarities.

That end result, however, is more than a decade away. And, because of the different routes to mobile maturity, the end states will still have significant differences.

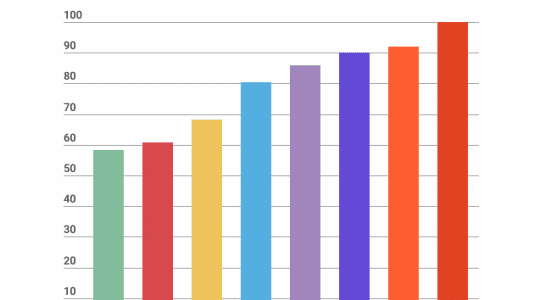

Global smartphone growth: diverging

What we see right now is simple: fast growth — and the potential for fast growth — in only two markets. India and Africa dominate net-new smartphone markets, but Africa is a few years away from fast growth. If you’re wondering where China is … it’s fast approaching maturity.

Global growth in smartphone shipments was slightly up to 4.3% in the first quarter of 2017, but it’s unevenly distributed:

Global growth in smartphone shipments was slightly up to 4.3% in the first quarter of 2017, but it’s unevenly distributed:

- India: 15% growth in Q1 2017 (source)

- Africa: 3.4% growth in 2016 (source)

- North America: 3% growth in 2016 (source); 4% in Q1 2017 (source)

- Europe: 2.4% growth in 2016, thanks entirely to Eastern/Central Europe; Western Europe is much lower (source)

- China: 1% growth rate in Q1 2017 (source)

Clearly, most of the world is in replacement mode. Rich countries (Europe, North America) and countries where smartphone penetration is high among those who can afford it (think China) are well penetrated and only buying replacement devices, mostly.

Two massive parts of the world are the entire hope for significant new growth for the smartphone industry: India and Africa.

India is the only major region actively in a massive growth phase still today, and its 1.3 billion people might be able to keep it there for a while. Africa, on the other hand, is perhaps one to three years away from that growth spurt — more wealth creation is required, even though the cheapest Chinese smartphones are starting to get really inexpensive.

Africa actually saw more feature phone sales last year than smartphones after five years of slowing feature phone sales and growing smartphone sales.

Mobile maturity models: 3 separate ecosystems

Globally what we’re seeing right now is three different types of markets, sometimes all intermingled within the same countries and regions:

Mobile Disruption

Mobile disruption is the model we’re most used to seeing in rich developed nations.

Mobile disruption is the model we’re most used to seeing in rich developed nations.

Wealthier nations had a desktop computing paradigm and a physical retail economy, and mobile is disrupting both. It’s already decimated some industries — think Amazon versus retail, or Uber/Lyft versus traditional cabs — but there’s also been a slow, tough slog against entrenched enterprises and brands.

For example, think of how slowly banking is being disrupted in North America and Europe, versus mobile creation markets like China and India where banking has been a mobile-only activity from day one for hundreds of millions of people.

Mobile Creation

Mobile creation is the model we see perhaps most clearly in China and India.

Mobile creation is the model we see perhaps most clearly in China and India.

There, no desktop computing paradigm existed on a large scale, people were largely unbanked, and massive penetration of mobile technologies could create entirely new industries in a mobile-first manner.

In some cases, the results mirror what we see in mobile disruption markets, but in many cases, China and India have come up with entirely new solutions, new ideas, and new vectors for innovation.

WeChat is probably the best example, despite the fact that it’s the most-used, because it has built a platform (WeChat) on a platform (Android/iOS) on a platform (smartphone/mobile) and perhaps even more spectacularly, entwined the formerly disparate concepts of apps and bots in itself.

PayTM is perhaps a good Indian example — it enables payments and booking of almost everything including bus tickets, hotels, and events. But India’s mobile economy has more inflow from Western apps and companies for two reasons: the country has a long history of English usage (which in some senses unifies a nation with 23 official languages), and politically, India is far more open to foreign companies than China.

Mobile emergence

Mobile emergence is the model we see in parts of Africa and other developing nations.

Mobile emergence is the model we see in parts of Africa and other developing nations.

Smartphones are coming, but feature phones are more common, as cost and connectivity are issues. Mobile is the key means of going online, as PC penetration is below 5% in key countries like Nigeria, but mobile means something entirely different.

While comparatively little of North America’s and Europe’s economy is mobile — m-commerce is growing fast, but is still about 3% of total retail sales in the U.S. — a staggering 25% of Kenya’s gross national product flowed through M-Pesa, a digital currency created by Vodaphone and Safaricom, as early as 2014.

That’s a very mobile-first ecosystem in a very feature-phone oriented country.

The key to mobile emergence economies is this: If they’ve accomplished so much on feature phones, what can we expect when they have smartphones? Massive innovation is virtually a given.

Global markets, local strategies

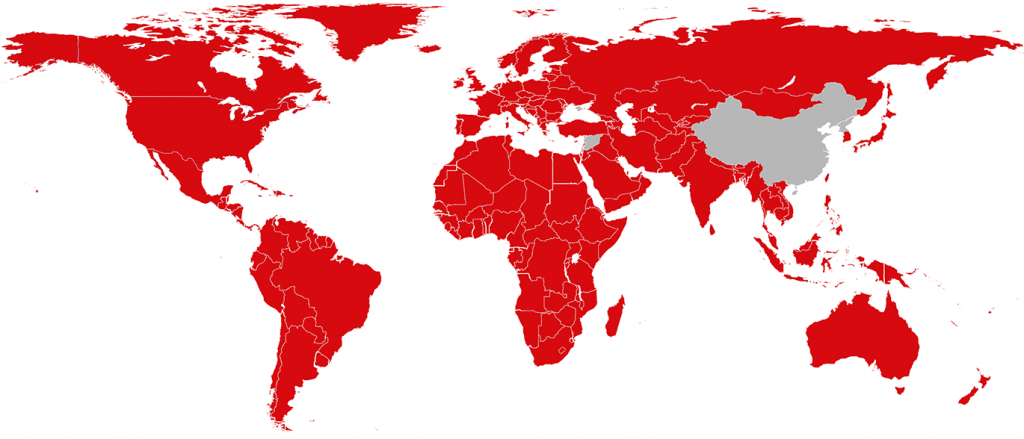

At a certain stage of growth, everything is global.

Amazon is targeting India for growth. Netflix is in available in over 190 countries. Uber is expanding to hundreds of global cities, and has been banned in dozens. Niantic’s Pokémon Go is global, and Japan’s LINE has is a top app in dozens of countries. China’s WeChat is expanding in Europe and elsewhere.

Countries Netflix is available in

As global as business gets, however, strategy remains local.

Uber’s finding partnerships with local companies in Russia and China sometimes works better than entering a market solo. China’s Tencent bought Supercell as a foothold in its ongoing international expansion. Rakuten bought Viber three years ago to grow beyond Japan. And Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp in the same time frame had some similar motivations: growth in places Facebook and Messenger were not heavily penetrated (at least at the time).

Those were all digital/mobile plays.

What we’re seeing now is that big enterprise and big brands are getting the mobile message, and competing not just for shelf space anymore, but mobile customers. As international expansion grows, the question is: are global mobile enterprises prepared for the changing conditions in different markets?

Facebook has shown it is.

Facebook works in mobile disruption and mobile creation markets, but Facebook Lite is perfect for mobile emergence. Marriott has done the same in the hospitality space, leading all hotel chains in mobile customers. Global sports and clothing brands Nike and Under Armour have done the same, leading all apparel brands in mobile users, with a staggering 121 million and 280 million respectively.

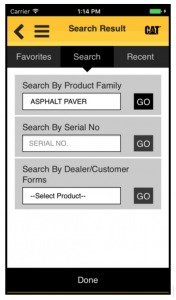

Oh, and in case you think it’s just about consumer brands, Caterpillar knows all about this too.

Almost 400,000 people are using Caterpillar apps on their phones, which they use not only to order parts, but also to inspect machinery for defects and servicing requirements. That makes an earth-moving company a mobile company, too.

MobileBest to GlobalBest: the martech stack you need

At TUNE, we’ve been talking about MobileBest for a while. It’s a pretty basic concept, but it’s exactly what global-scale brands and enterprises need for local success, globally.

Very simply, it means what’s best for the customer is what’s best for the brand.

It’s not mobile first, necessarily, and it’s not mobile only. It’s apps, sure, but it’s also mobile web. It’s push messaging, absolutely, but it might also be SMS in an emerging market. It’s bots in messaging apps, perhaps, and it’s an Alexa skill to go with your smart home appliance, sure, but it’s also, at times, real-world live and local solutions, as customers request them.

The question quickly becomes: what kind of marketing technology stack supports these requirements?

As global enterprises push into local markets, they need to adapt to local requirements in addition to offering innovation that they’ve developed elsewhere. That means the channels, the methods of communication, the means of marketing, and the ways of providing customer service might all change.

WeChat’s opening screen

In other words, some elements of your marketing tech stack may diverge from country to country. You might do customer support via WeChat in China, for instance, but via your own app in the U.S. You might accept payment via Paytm in India, and PayPal in the UK.

One thing, however, stays the same.

Customers are people, and marketing needs to be people-centric.

That’s exactly why TUNE just released TUNE People Service. You’re not selling to devices, or to locations, or to demographics, or to psychographics. All of those can help when targeting, but ultimately, you’re selling to people. Connecting every engagement to a person, whether a prospect or a customer, is key to understanding impact.

Knowing each customer individually on a worldwide scale across platforms, through their journeys, and past the point of purchase is key is to global growth in the coming era of mobile ubiquity.

Author

Before acting as a mobile economist for TUNE, John built the VB Insight research team at VentureBeat and managed teams creating software for partners like Intel and Disney. In addition, he led technical teams, built social sites and mobile apps, and consulted on mobile, social, and IoT. In 2014, he was named to Folio's top 100 of the media industry's "most innovative entrepreneurs and market shaker-uppers." John lives in British Columbia, Canada with his family, where he coaches baseball and hockey, though not at the same time.